Walking into the new NYPD Police Academy at 6:15 a.m. on May 15, 2015, is the closest I’ll ever get to visiting Starfleet Academy. As I look for the classroom to sit in on the department’s new “Smart Policing” training, I wander down a mammoth hallway that I literally could have driven a Mack truck down. Recruits walk swiftly in their black and gray uniforms, carrying duffles with a nightstick strapped to the top. As I pass the muster field—back on East 20th, it was a muster deck—cadets are lined up in formation; goslings splash around in a pond that reminds me of a moat.

At the end of the hall, I see a young, black, female recruit stop and salute stand-up posters of Officer Brian Moore, whose funeral I’d attended a week before, and Officers Rafael Ramons and Wenjian Liu, who were killed in Brooklyn’s 84th on Dec. 20, 2014, by Ismaaiyl Abdullah Brinsley, supposedly as retaliation for the deaths of Garner and other unarmed black men, before running into the subway and committing suicide. Those executions came soon after a Staten Island grand jury declined to indict officers in the Garner death, leading police union President Patrick J. Lynch said there was “blood on many hands,” including that of Mayor de Blasio and on the steps of City Hall.

Four police officers—one white, one Hispanic, two black—welcome me to the classroom to observe the “Smart Policing” segment of a new three-part 20K Training Initiative that was accelerated after Garner’s death, which brought accusations of escalating a non-violent stop, using an unauthorized chokehold to make an arrest and then failing to provide assistance to an offender who was begging for help, saying “I can’t breathe 11 times.”

Under pressure to improve their training after the Garner incident, the Commissioner William Bratton’s team at One Police Plaza figured out that officers were getting virtually no updated training, especially on tactical maneuvers such as takedowns in what they call “non-violent, non-confrontational” arrests since they’d initially attended the academy. That meant that an officer on the street might not have gotten any physical training updates, other than on firearm use, in 30 years, even as the department banned the use of chokeholds 20 years ago. (The officer who took down Garner, Daniel Pantaleo, was 29 and had been on the force since 2006—the height of the stop-and-frisk era.)

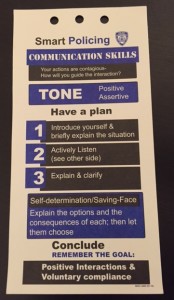

The department launched the first 20K trainings in December; it is divided into three separate trainings of a day each: “Foundations,” philosophical training using “Blue Courage” modeled on the “Seven Habits of Effective People,” but for cops; the new Smart Policing, which teaches strategies for improving communications and emotional intelligence, de-escalating encounters and avoiding cursing members of the public; and Tactics, a physical training on how to correctly take down suspects without the use of deadly force.

Ricky Taggart, who had been on the force 30 years as of April 12, kicks off the “Smart Policing” training of Team P, which includes officers from the 46, 68, 81 and 101, as well as two special units. Dressed in perfectly pressed brown slacks with a shirt and tie under a fitted beige vest, and several gold rings and a bracelet, Taggart quickly works to set a balanced tone to the diverse, in age, ethnicity and gender, group of cops.

Taggart starts positive. “We are the best in the world at what we do, but there’s something we lost along the way.” That is, he says, “the way we talk to each other, our community and our own families.” While most cops are already experts in dealing with the public, they still need to work to be better. We have to because we have a new enemy,” he says, holding up his cell phone. “This affects the public’s view and perception of how we do our jobs.

Taggart spoke of NYPD Det. Patrick Cherry who cursed and yelled at an Uber driver—a tirade caught on video, leading to Cherry losing his gun and badge, being removed from an FBI task force and being assigned to desk duty. “Sure, he’s a great guy, but what did it cost him?” he asks.

“Smart Policing” includes photos of Peyton Manning of the Denver Broncos and Kevin Durant of the Oklahoma Thunder to convince the cops they need to be here. “How many hours do you think he has to put in to practice his craft?” Taggart asks about Manning.

Taggart and other trainers talk bluntly to the cops about management, such as when they bark orders rather than saying, “Let me help you,” adding, “That’s a leader.” He talks about six unnamed captains who “walked by me like I was dirt,” officers not returning a “good morning” and recalls one of the condensed one-day “Smart Policing” trainings that commanders are required to take. A chief was upset earlier this year because there wasn’t a reserved spot for him near the door of the academy. His conclusion? “Egotistical” and “unprofessional.”

The officers seem the most engaged when Taggart and other trainers get real. Taggart slams the pressure of the stop-and-frisk era “of the last 10, 15 years” when the brass took away officers’ discretion to make smarter arrests, instead demanding endless numbers. In addition, the department wasn’t helping officers deal with the stress of the demands. “In 30 years, the department never talked to us about that,” Taggart says.

The training includes a video of Bratton, which draws snickers when he says “smot” (smart) and “potners” (partners) with his Boston accent, even as it includes a subtle threat, mixed with praise. “Brutal force is very rare in the NYPD, and we’re weeding out the few officers who engage (in it). There’s no place for them here,” he tells the officers. He says the training will help them deal with emotions and “how to avoid profanity,” which he says draw 30 percent of Civilian Complaint Review Board complaints. He wants “helpful, friendly service,” he tells them, adding that the department had taken people skills for granted in the past, but is now focused on ensuring that the training is there. “You count, you matter,” he assures them.

Taggart reminds the cops that bad policing by a few “stigmatizes all of us,” yet the 35,000 cops of the NYPD are the “most restrained in the country.” (This is especially true of firearm use, department data show.)

Mid-morning, Jesus Ramos takes over, wearing a gun on his plain-clothed hip. He presents the crisis and conflict segment designed, in part, by hostage negotiators. In a video, Lt. Jack Cambria, of the Hostage Negotiation Team, tells them not destroy their careers “for a moment of indiscretion,” and to learn to control their emotions.

Using images of hostage negotiators talking people out of jumping off buildings, Ramos reminds them an irate citizens is not lodging a “personal attack,” and to respond with “you seem upset” to de-escalate the exchange. Engage active listening, allow them to vent, and learn to have empathy, not sympathy, so you can conclude the interaction peacefully.

Ramos discussed the need for good body language—no crossed arms—and the need to learn to “be nice” and smile more often to gain influence in non-violent exchanges.

Over a short break, a black officer comes over to me and tells me he’s skeptical about the training. “You can’t always smile,” he says when you’re worried about staying alive. I remind him that the training is about non-violent situations, but he doesn’t seem convinced. He also seems on edge about all cops being stereotyped by the bad apples on the force. Doctors who give bad breast implants don’t represent all doctors, he tells me.

Frank D’Antuono, a white officer with his gun tucked into his pants, talks to the officers about the responses they should take in non-violent, non-confrontation situations, explaining that the department is now emphasizing communication. Of the trainers, he seems the most concerned with what officers think about it, perhaps because more of them seem openly skeptical by then, even as others listen intently. “One percent of 1 percent need this training more than anything else,” he explains. “Winning equals voluntary compliance.”

He presents the department’s new advice to look for external help if the offender doesn’t want to comply with the office, including a bystander or a relative or friend—”if they’re on your side,” he adds. For instance, in the Garner case, the officer might have asked a bystander to help reason with him rather than going with the chokehold as the first option. He advises them to not “draw a line in the sand” that sets up an escalation, such as “Call me dude one more time!”

Then the training becomes a study in mindfulness. Officers must watch their “adrenaline dumps,” and focus on their breathing instead, especially in situations, such as protests, where they’re being cursed, like “Fuck you, pigs!” He says it’s a good idea to rotate officers in and out of a protest barricade, so they have time to breathe through the stress. Importantly, he says, “adrenaline, anger and fear are all controllable”; officers don’t have to get “all jammed up” if they work to quiet their minds. He uses Det. Cherry as an example again: his anger at the Uber drive was “controllable,” he says. He didn’t have to get suspended: “don’t be that guy.

D’Antuono also talks about phone cameras and how they are also helping the cops, including to help identify suspects who abuse cops, such as after a bunch of white hipsters on Ludlow Street attacked an officer after the bars closed. Cameras help “call B.S.” on false eyewitness accounts, he adds. “I can’t wait until we have body cameras. I can’t wait.”

After lunch in the cafeteria, I ride back up in the elevator with several male cops from our class who are laughing about the training and especially the instruction to “be nice.”

“My favorite part was to get a relative to help,” another says.

“What, we’re supposed to call his cousin!?”

Then a large man in front of me with graying hair lets loose: “I thought I was the only one who thought this whole thing is ridiculous.” They all laugh as the doors open. Back in the classroom, one of the trainers preps me for the next session. “We do apologize if you’re offended by the cussing,” he says. I assure him that I’m not.

Read about the cursing segment here.

Leave a Reply